Echinoderm

The echinoderms ( echino means "spiny;" derm means "skin") are large, conspicuous, entirely marine invertebrates. Today, this group inhabits virtually every conceivable oceanic environment, from sandy beaches and coral reefs to the greatest depths of the sea. They are also common as fossils dating back 500 million years. These less-familiar fossil types are represented by a bizarre variety of animals, some of which reveal their relationship to the living echinoderms only at close inspection.

Diversity

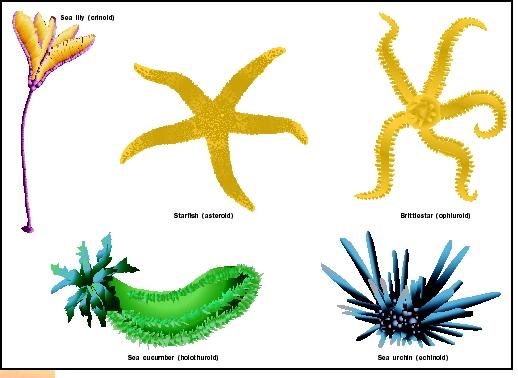

The species living today are generally regarded as belonging to five subgroups: sea lilies and feather stars (Crinoidea, 650 species); starfish (Asteroidea, 1,500 species), brittlestars and basket stars (Ophiuroidea, 1,800 species), sea cucumbers (Holothuroidea, 1,200 species); and sea urchins and sand dollars (Echinoidea, 1,200 species).

Sea lilies have a central body, or calyx, surrounded by feathery, usually heavily branched arms. This whole arrangement sits at the end of a stem-like stalk attached to the sea bottom. The feather stars lack this stalk. Starfish (also called sea stars) have a central disk that is not marked off from the unbranched arms, of which there are usually five. Occasionally, one will encounter starfish species with more than five arms. Brittlestars also typically have five relatively long, flexible arms, but these are well differentiated from the central disk.

Sea cucumbers are soft-bodied and wormlike, with a cluster of tentacles around the mouth at one end. Sea urchins usually have a rigid body of joined plates upon which is mounted a dense forest of spines. The sea urchin body can be almost spherical, with long spines, or flattened to varying degrees with very short spines in types such as the sand dollars.

Anatomy and Physiology

In general, echinoderms are characterized by several unique features not found in any other animal phylum . They have a limestone (calcium carbonate) skeletal meshwork called "stereom" in their tissues, especially the body wall. The porous structure of stereom makes the skeleton light yet resistant to breakage. Echinoderms possess a special kind of ligament that can be stiffened or

Males and females are separate, and fertilized eggs develop into a typically free-swimming larva that changes (or "metamorphoses") from a bilaterally symmetric form to an adult possessing a body structure with the five radiating rays that makes adult echinoderms so distinctive. Even the worm-like sea cucumbers and sea lilies show this five-part structure because the feeding tentacles and arms are usually present in multiples of five.

Echinoderms are relatives, although distant ones, of the vertebrates. Like vertebrates, and unlike other animal phyla, echinoderms are "denterostomes," meaning the mouth pore forms after the anal pore during early development. This makes them ideal subjects for studies that shed light on human development and evolution. In addition, the ecological importance of echinoderms, combined with their sensitivity to environmental degradation, gives them a key role to play in environmental research.

SEE ALSO Animalia ; Coral Reef ; Development

Richard Mooi

Bibliography

Hyman, Libbie Henrietta. The Invertebrates, Vol. 4: Echinodermata. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1955.

Lawrence John M. A Functional Biology of Echinoderms. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins, 1987.

Mooi, R., and B. David. "Skeletal Homologies of Echinoderms." Paleontological Society Papers 3: 305–335.

Nichols, David. Echinoderms. London: Hutchinson, 1962.